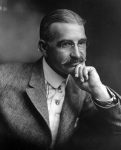

L(yman) Frank Baum (1856-1919) was an American journalist and writer whose best-known book is The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900). Baum’s stories about the imaginary Land of Oz belong to the classics of fantasy literature.

L(yman) Frank Baum (1856-1919) was an American journalist and writer whose best-known book is The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900). Baum’s stories about the imaginary Land of Oz belong to the classics of fantasy literature.

Baum was born in New York, the son of an oil magnate and a women’s rights activist, and the brother of seven siblings. He was raised on a large estate just north of Syracuse which, although it was large, did not have running water. Until the age of twelve, Baum was privately tutored at home.

Before publishing his first novel, Baum spent two years in the late 1860s at Peekskill Military Academy, whose rigid discipline he loathed. In 1873 Baum became a reporter on the New York World. Two years later he founded the New Era weekly in Pennsylvania. He was a poultry farmer with B.W. Baum and Son, and edited Poultry Record and wrote columns for New York Farmer and Dairyman. Baum’s father owned a string of theatres and Baum left journalism to earn his living as an actor. In New York he acted as George Brooks with May Roberts and the Sterling Comedy in plays which he had written. He owned an opera house in 1882-83, and toured with his own repertory company. In 1882 he married Maud Gage; they had four sons.

Baum made his debut as a novelist with Mother Goose in Prose (1897), based on stories told to his own children. Its last chapter introduced the farm-girl Dorothy. Over the next 19 years Baum produced 62 books, most of them for children. Father Goose: His Book (1899) quickly became a best-seller.

Baum’s next work was The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Illustrated and decorated by W.W. Denslow, the book was published at Baum’s own expense and sold 90,000 copies in the first two years. Upon his success, Baum moved to California, where he produced sequels for the rest of his life. Despite its popular success, the Oz series was long shunned by librarians and neglected by scholars of children’s literature. In his introduction to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, he describes the story as ushering in a new (and significantly less horrifying) era of children’s fiction:

“Yet the old-time fairy tale, having served for generations, may now be classed as ‘historical’ in the children’s library; for the time has come for a series of newer ‘wonder tales’ in which the stereotyped genie, dwarf, and fairy are eliminated, together with all the horrible and blood-curling incident devised by their authors to point a fearsome moral to each tale. Modern education includes morality; therefore the modern child seeks only entertainment in its wonder-tales and gladly dispenses with all disagreeable incident.”

Under the pen name “Edith Van Dyne” he published 24 books for girls, and as “Floyd Akers” he wrote six books for boys. “Schuyler Staunton” was reserved for the novels The Fate of the Clown (1905) and Daughter of Destiny (1906).

The first of the Oz books was made into a musical in 1901, but Baum was determined to see his stories also on the screen. Since the first Oz book was published, the tale has been filmed many times. The Patchwork Girl of Oz was made in 1914, and Baum himself participated in the project. In 1914-15 Baum was the founding director of Oz Film Manufacturing Company (later Dramatic Features Company), a well-equipped seven-acre studio on Santa Monica Boulevard in Los Angeles. The venture failed, and produced only two more Oz stories, His Majesty the Scarecrow of Oz, and The Magic of Cloak of Oz.

The most famous film version from 1939 was directed by Victor Fleming, starring the sixteen-year-old Judy Garland. It received an Academy Award nomination for Best Picture and was selected to the National Film Registry at the Library of Congress. However, all reviews were not positive. Russell Maloney wrote in the New Yorker (August 19, 1939): “I say it’s a stinkeroo. The vulgarity of which I was conscious all through the film is difficult to analyze. Part of it was the raw, eye-straining Technicolor, applied with a complete lack of restraint.” In general the 1939 version of The Wizard of Oz was not well received; it achieved its present status after TV showings in the 1950s.

The film can be interpreted in many ways; a search for happiness at the end of the Yellow Brick Road, Oz represents Hollywood, to which teenage girls dream of running, in hopes of breaking into movies. Dorothy’s journey can be seen as a young girl’s last childhood experience, and when she chooses to return home to Kansas, she has matured into a young woman, or has abandoned her childhood world of imagination. Baum wanted the children to see that the traditional American values of integrity, self-reliance, candor, and courage would make them succeed despite obstacles. Noteworthy, his stories carry a pacifist plea for tolerance between people. Henry Littlefield argued in his article ‘The Wizard of Oz: Parable on Populism’ (American Quarterly, 1964) that Baum’s work was a political allegory. At its center were the Western farmer-activists who wanted the government to produce more money so that they could pay off their debts more easily. (see The Historian’s Wizard of Oz: Reading L. Frank Baum’s Classic as a Political and Monetary Allegory, ed. by Ranjit S. Dighe, 2002) Thus the Yellow Brick Road was the gold standard, the Scarecrow was the farmer, the wicked Witch of the East was Wall Street and Big Banks, etc.

Some of Baum’s books for adults, including The Last Egyptian (1908), dealt with other counties and places. He gathered material for works aimed at teenagers during his motoring tours across the country and travels in Europe and Egypt. Born with a congenitally weak heart, Baum was ill through much of his life. He died on May 6, 1919, in Hollywood, where he had moved to a house he called Ozcot.

The Oz series did not stop. Ruth Plumly Thompson was commissioned by Baum’s publisher to write 21 titles. Other writers include Baum’s great-grand son Roger Baum. The Laughing Dragon of Oz (1934) was composed by Frank Joslyn Baum, the author’s son, but he did not have a legal right to publish the book. Salman Rushdie’s The Wizard of Oz (1992) deals with the classic film adaptation against the background of universal symbols and myths.

(Edited from Baum’s entry at Books and Writers. Click the link for the full article.)